The One-Year Myth: Why Your Grief Doesn’t Have an Expiration Date

One of the pernicious myths regarding grief is that something happens at the end of the first year following a loved one’s death where the griever miraculously feels “better.” When this does not occur, they may look at the calendar with a sense of impending failure, asking some version of the same question: “Why don't I feel better yet? Am I doing this wrong?”

We have a cultural obsession with the "one-year" milestone. We treat it like a finish line—a magical threshold where the heavy lifting of mourning should be complete and we should "return to normal."

But here is the clinical truth: The one-year mark is often one of the hardest parts of the journey, not the end of it.

Why the "One-Year" Timeline is a Fiction

The idea that grief fits into a neat 365-day box is not based on human psychology; it’s based on a calendar. In reality, the first year is often spent in a state of "survival shock." Your brain is busy rewiring itself to a world that no longer contains your loved one.

When that first anniversary hits, the "protection" of shock often wears off. You aren't "backsliding" if you feel more pain at fourteen months than you did at four; you are simply more present for the reality of the loss.

Grief is Not a Task to Finish

Instead of a staircase we climb (where the top is "recovery"), think of grief as a landscape you learn to live in.

You don’t "get over" it: You grow around it.

Progress isn't linear: It looks more like a scribble than a straight line.

The "Second Year" is real: Many people find the second year more challenging because the initial casseroles have stopped arriving, the check-in texts have slowed, and the permanent nature of the loss finally sinks in.

If you are past the year mark and still feeling the weight of your loss, you aren't "stuck." You are grieving. And grieving is a testament to the depth of the love that preceded it.

A Note on the "No Major Decisions" Rule

You’ve likely heard the well-meaning advice: “Don’t make any major life changes in the first year.” While this is designed to protect people from impulsive choices made in a while we’re experiencing brain fog, it isn't a universal law.

For some, staying in the family home is a source of daily trauma. For others, a career change or a move provides a necessary "fresh start" that aids their healing. Clinical wisdom suggests we should pause and evaluate, but we shouldn't paralyze ourselves. If a decision is born out of a need for safety, peace, or survival, "waiting out the clock" isn't always the healthiest choice. Sometimes, the most empowered thing you can do is trust your own internal compass, even when the world tells you to wait.

When the Calendar Becomes a Minefield: Grief and the "Minor" Holidays

We often talk about the "Blue Christmas" phenomenon—the way the heavy hitters of the holiday season amplify a sense of loss. But there is a quieter, sharper kind of pain that arrives with the holidays that focus on a specific relationship. When the world turns pink and red for Valentine’s Day or fills with floral tributes for Mother’s Day, the grief isn't just general; it’s targeted.

The Specificity of the Sting

For someone who has lost a spouse or significant other, Valentine’s Day can feel like a cruel performance of what they no longer have. It’s a day built on the assumption of a "plus one." Similarly, Mother’s Day or Father’s Day after the death of a child creates a surreal disconnect. You are still a parent, but the traditional ways of celebrating that identity have been severed.

These holidays are difficult because they are inescapable. You see them in the grocery store aisles, in your email inbox, and across every social media feed. They demand a celebration of a bond that, for you, is now defined by absence.

Navigating the "Happy” Hallmark Moment

One of the hardest parts of these days is the well-meaning stranger or acquaintance who offers a cheerful greeting. When your heart is breaking, being told to have a "Happy" anything can feel like a physical blow.

How do you respond when someone says "Happy Mother’s Day" or "Happy Valentine’s Day" and you’re struggling to stay afloat? The most important thing to remember is that you are allowed to opt-out. If Valentine’s Day feels like too much, stay off social media and treat it like any other Tuesday. It’s also important to be gentle with yourself. Grief is exhausting. You don't need to be strong or "get over it." Just getting through the day is enough. Your grief is a testament to the love you shared, and you get to decide how—or if—you want to mark the day.

The "How Are You?" Trap: Navigating the Social Squeeze

As a grief therapist, I’ve learned that one of the most challenging experiences for people experiencing grief is when a well-meaning friend or acquaintance ask, “So, how are you doing?”

I tend to describe such situations as the “How Are You?” Trap.

It’s a trap because it presents an impossible choice. On one hand, the truth is heavy—you might be barely holding it together, or perhaps you haven’t slept in three days. On the other hand, the social contract suggests you should say, "I’m fine," and move on.

Why This Simple Question Feels So Heavy

When you are grieving, your "social battery" is often running on a 5% charge. Providing a real answer requires an emotional vulnerability you may not have the energy for. Conversely, giving the "polite" answer can feel like inauthentic and a denial of your pain. It creates a sense of cognitive dissonance—you are performing "okayness" while your internal world is in ruins.

Strategies for the Social Squeeze

If you find yourself stuck in this loop, remember that you are not obligated to be an open book for everyone you encounter. Here are some ways we can handle the "trap":

The Tiered Response: Categorize people into "Inner Circle" and "Outer Circle." For the Outer Circle (colleagues, casual neighbors), it is perfectly okay to use a polite shield: "I’m taking it one day at a time, thanks for asking."

The Pivot: Acknowledge the question briefly, then reclaim the conversation. "It’s been a bit of a rollercoaster, but I’m hanging in there. How is your family?"

The Radical Truth: With your Inner Circle, give yourself permission to be "not fine." A simple, "Actually, today is a really hard day," can invite the specific support you actually need.

Grief is a marathon, not a sprint. You don’t owe the world a performance of "healing." Protect your energy, choose your confidants wisely, and remember it is perfectly okay to save your true heart for the people who have earned the right to see it.

Mapping a New Reality: Assimilation, Accommodation, and Sudden Loss

When you lose someone suddenly—to an accident, a suicide, or a medical emergency—it feels like your world has been physically torn apart. In the aftermath, you might feel like your brain is "glitchy" or that you are losing your mind. The reaction is understandably because you are not just carrying sorrow; you are carrying a shattered world.

In psychology, we use two concepts to explain why your mind feels this way: Assimilation and Accommodation. Understanding these can help you be more patient with yourself as you navigate this impossible terrain. In doing so, we are not seeking to “get over” our grief. Rather, we are learning to build a new mental house large enough to hold both the love you have for the person who died and the loss you are enduring.

Understanding the Cognitive Collision

When we experience a loss, our internal "schema"—the mental map of how the world works—is suddenly at odds with a new, brutal reality.

The Old Schema: "I will grow old with my spouse," or "My child is safe when they leave the house."

The New Reality: The person is gone, and the world is no longer predictable.

Assimilation: Trying to Fit the Loss into the Old World

In the early time period of sudden grief, the mind attempts assimilation. This is the process of trying to fit new, terrifying information into existing schemas without changing the internal map.

In the context of sudden loss, assimilation often manifests as:

Disbelief and Denial: "I keep expecting them to walk through the door."

Searching Behaviors: Scanning crowds for their face or smelling their clothes to maintain their presence.

Ruminative Guilt: The "if onlys." By blaming themselves, the client is often trying to preserve the schema that the world is controllable and fair.

Clinical Insight: We shouldn't rush to "correct" these behaviors. Assimilation is a protective buffer. It is the mind’s way of sipping tragedy in small doses because the full reality is too toxic to swallow at once.

Accommodation: Redrawing the Map

Accommodation occurs when the new information is so massive that the old schema must be completely altered to account for it. This is the "heavy lifting" of grief work. For a survivor of a suicide or accident, accommodation means acknowledging: "The world is not always safe, and I cannot control everything—but I must find a way to live in it anyway."

This involves:

Reconstructing Identity: Moving from "we" to "I."

Integrating the Narrative: Accepting the "before" and "after" as part of one continuous, albeit scarred, life story.

How We can Support Ourselves in the Moment

It may be helpful to visualize your mind as a a GPS map (i.e., a mental map). Before the loss, your map was programmed with certain "rules": If I call, they will answer. When I go home, they will be there. The world is generally safe.

A sudden loss is like a massive earthquake that destroys the landscape. Your GPS is still trying to follow the old roads, but the roads are gone. Accommodation is the difficult, slow process of updating your GPS. You aren't erasing the old map; you are drawing a new one that includes the reality of the loss. Here some tips to navigate the new map.

Lower Your Expectations: Your "processing power" is being used up by this massive mental update. It is okay if you are forgetful, tired, or overwhelmed by simple tasks.

Stop Fighting the "Glitches": If you catch yourself expecting a phone call from them, don't judge yourself. Just gently remind your heart, "That’s my old map. I’m still learning the new one."

Find Small Anchors: When the world feels unpredictable, stick to small routines (like a morning cup of tea) to give your brain a sense of stability.

If you are interested in the role our brain plays in grief, I highly recommend Mary-Frances O’Connor’s The Grieving Brain.

Learning to be Curious About Our Emotions

There is a quote, often misattributed to Walt Whitman, urging us to "be curious, not judgmental." Most of us recognize this as a tool for interpersonal harmony—a way to pause before reacting to a difficult colleague or a grieving friend. But the most transformative application of this concept isn’t necessarily outward; it’s inward.

When we experience emotions such as anger, deep sorrow, or even numbness, our instinct is to label them. We tell ourselves, "I shouldn't feel this way," or "This is a bad emotion." This judgment creates a secondary layer of suffering. Instead, curiosity invites us to treat our emotions as data, not directives.

Emotions as Information

Psychological research, such as the work on Affective Realism and Emotional Granularity by Dr. Lisa Feldman Barrett, suggests that our brains construct emotions as guesses about what is happening in our bodies and the world. From this perspective, an emotion isn’t "good" or "bad"—it is a signal.

Anger might be a signal that a boundary has been crossed.

Guilt might be an invitation to examine our values.

Deep Sadness is often a testament to the depth of our love.

The Power of being an Emotion Scientist, Rather than an Emotion Judger

Studies on mindful emotion regulation highlight that observing emotions without judgment—a core tenet of curiosity—actually reduces their physiological intensity. When we ask, "Where do I feel this in my body?" or "What is this feeling trying to protect?" we shift from being overwhelmed by the wave to becoming the observer of the tide.

By replacing "Why am I like this?" or “this emotion is bad, I shouldn’t feel it” with "what is this emotion trying to tell me?" we create the space necessary to choose our next step, rather than reacting out of habit.

Next time a difficult emotion arrives, try to greet it like a messenger. You don't have to like the message, but being curious about its contents might help you discern what you need in the moment.

The Hidden Sting of Silver Linings: Why Sympathy Can Fall Short in Grief

Following the death of a loved one, we must navigate the raw, often chaotic landscape of loss. In these tender spaces, well-meaning friends and family often reach for comfort, and frequently, they offer what I call "silver lining sympathy." It’s the desire to make things better, to find the bright side, and to offer reassurances like, "At least they're not suffering anymore," or "they are in a better place." While these statements may come from a place of love (or perhaps the person’s own discomfort with death), they often inadvertently leave the grieving person feeling even more isolated and misunderstood.

Brené Brown, in her powerful explorations of vulnerability, distinguishes beautifully between sympathy and empathy. Sympathy, she explains, often involves feeling for someone from a distance, frequently accompanied by a desire to fix or minimize their pain. Empathy, on the other hand, is about feeling with someone, stepping into their shoes, and acknowledging their pain without judgment or an agenda to change it.

When we offer silver lining sympathy, we are, in essence, trying to pull someone out of their grief rather than sitting with them in it. Imagine someone has lost a child, and a friend says, "At least you have your other children." While factually true, this statement completely bypasses the profound, unique pain of losing that child. It implies that their current sorrow is somehow invalid or should be lessened by other blessings. Grief doesn't work that way. It's not a linear equation where one positive cancels out a negative.

The grieving heart needs to be seen, heard, and validated in its present pain, not redirected to future possibilities or past good fortune. It needs someone to say, "This is incredibly hard, and I'm so sorry you're going through this," or simply, "I'm here." It needs presence, not platitudes.

As difficult as it can be to witness someone’s suffering, true support often means resisting the urge to fix it. Instead, we can offer the powerful gift of empathetic presence. It’s about being a container for their sorrow, holding space for their anger, confusion, and despair without feeling the need to sprinkle it with silver linings. In doing so, we help them feel less alone in their darkest hours, which is, perhaps, the most profound comfort of all.

The Quiet Strength of "Weak Ties": Connecting When It Matters Most

As a therapist, I often work with individuals navigating significant life challenges: the profound ache of grief, the heavy shroud of depression and anxiety, and the quiet struggle of social isolation, particularly for our senior population. In these times, we naturally lean on our "strong ties" – our closest family and friends. These relationships are invaluable, offering deep emotional support and understanding.

However, there are significant, often overlooked, benefits to nurturing our "weak ties", a concept first explored by sociologist Mark Granovetter. These are the less intimate connections in our lives: the person with whom you briefly chat while walking your dog, the checkout person at the grocery store, or the barista who knows your coffee order. While these exchanges may not offer the same depth of emotional connection as a strong tie, these encounters can be incredibly powerful, especially when we're at our most vulnerable.

For those grieving, weak ties can provide a gentle distraction without the pressure of intense emotional processing. A brief, casual conversation can offer a momentary respite from your deep sadness or a pleasant, low-stakes interaction that doesn't demand you "be okay."

Individuals grappling with depression and anxiety often find the demands of strong ties overwhelming. The fear of burdening loved ones or the energy required for deep emotional engagement can be exhausting. Further, depression and anxiety are pernicious in encouraging us to isolate when, in fact, social connection is often key to our emotional health. Weak ties offer a lighter form of connection. A quick chat at the grocery store or a shared laugh with a distant colleague can provide a sense of belonging and normalcy, boosting mood without the pressure of deep disclosure. These small, positive interactions can be crucial steps in rebuilding confidence and reducing feelings of isolation.

For seniors experiencing social isolation, weak ties can be a lifeline. Retirement, mobility issues, or the loss of loved ones can significantly diminish strong social circles. Engaging with weak ties – a friendly wave to a neighbor, a conversation at a community center, or even a brief exchange with a delivery person – can combat loneliness, stimulate cognitive function, and provide a sense of routine and connection to the wider world. These interactions affirm their presence and value in the community.

In essence, weak ties offer a different kind of support – less intense but no less significant. They provide a broader network of casual interactions that can weave a protective net around us, offering moments of lightness, practical help, and a gentle sense of belonging when strong ties alone might feel insufficient or overwhelming.

To read more about the benefits of weak ties and grief, here is a link to one of my favorite grief websites, whatsyourgrief.org.

The Fresh Start Fallacy: How New Year’s Resolutions Adversely Affect our Mental Health

It seems inevitable that, as New Year’s approaches, we often contemplate resolutions designed to somehow improve our lives.While the cultural narrative frames these goals as a pursuit of excellence, clinical research indicates that traditional resolution-setting often functions as a catalyst for diminished self-efficacy and heightened anxiety.

This phenomenon is largely driven by the "False Hope Syndrome." Individuals frequently set goals that are unrealistic in their scope or timeline, fueled by the temporary "high" of a new calendar year. When the inherent difficulty of behavior change meets the reality of January’s environmental stressors—such as post-holiday depletion and limited daylight—the resulting inability to meet our goals is often internalized. Rather than viewing a setback as a logistical hurdle, many people interpret the setback as a fundamental character flaw, reinforcing a "failure identity."

Further, resolutions tend to promote dichotomous (all-or-nothing) thinking. This cognitive distortion creates a rigid framework where a single lapse signifies a total collapse of the objective. This rigidity doesn't just halt progress; it triggers a cycle of shame and self-criticism that can exacerbate symptoms of depression and social withdrawal. When goals are born from "introjected regulation"—the feeling that one should change to avoid guilt—rather than intrinsic desire, the psychological burden becomes unsustainable.

To safeguard mental health, we must shift the clinical focus from radical transformation to incremental, sustainable intentions. By prioritizing psychological flexibility over rigid benchmarks, individuals can foster genuine growth without the collateral damage of self-loathing. As we move through the first quarter of the year, the goal should be to treat ourselves with the same clinical compassion we would offer a friend, replacing high-pressure mandates with manageable, value-aligned actions.

Pregnancy Loss and Grief

There is an urban legend about Ernest Hemingway betting his fellow writers that Hemingway could craft a full story in six words. After the bet was accepted, Hemingway wrote, “For Sale, Baby Shoes, Never Worn.”

Regardless of the story’s origins, I think it captures the deep grief that arises from pregnancy loss (the clinical terms are “reproductive grief” or “reproductive trauma” which includes not only pregnancy loss but also the grief arising from infertility).

As a grief therapist, I have supported individuals through the depths of grief following death and loss. One area that consistently demands more recognition and understanding is grief following pregnancy loss. Whether it's an early miscarriage, a stillbirth, or the heartbreaking conclusion of infertility, the pain is profound, yet often profoundly minimized by society. This minimization of pregnancy loss and reproductive trauma results in disenfranchised grief.

Disenfranchised grief refers to any loss that is not openly acknowledged, publicly mourned, or socially supported. Pregnancy loss fits this definition tragically well. There's often no funeral, no official mourning period, and sometimes, even the language to articulate the enormity of the loss feels inadequate. A parent's arms ache for a child they never held, a future they envisioned, and dreams that were shattered in an instant. Yet, they might be met with well-meaning but hurtful phrases like, "At least you can try again," or "It wasn't a real baby yet." These words, though perhaps intended to comfort, only serve to invalidate the very real bond that was formed and the deep grief that remains.

The impact of this disenfranchisement can be devastating. Individuals experiencing pregnancy loss may feel isolated, ashamed, and as if their grief is somehow "wrong" or unwarranted. They might struggle to process their emotions, feeling compelled to "get over it" quickly and silently. This lack of external validation can lead to anxiety, depression, and PTSD.

Our society has a collective responsibility to change this narrative. We must create spaces where this grief is seen, heard, and honored.

If you are experiencing pregnancy loss, please know that your grief is valid. It is real. You have every right to mourn the loss of your child and the future you envisioned. Seek out support – whether it's a therapist specializing in reproductive loss, a support group, or trusted friends and family who can simply listen without judgment.

And for those supporting someone through pregnancy loss, remember the power of presence and validation. Instead of trying to "fix" their pain, it is important to acknowledge someone’s grief and loss. Allow the person who is grieving the space and time to grieve in their own way, for as long as they need. By doing so, we begin to chip away at the disenfranchisement, allowing people to cope with their grief and learn to integrate the grief into their lives.

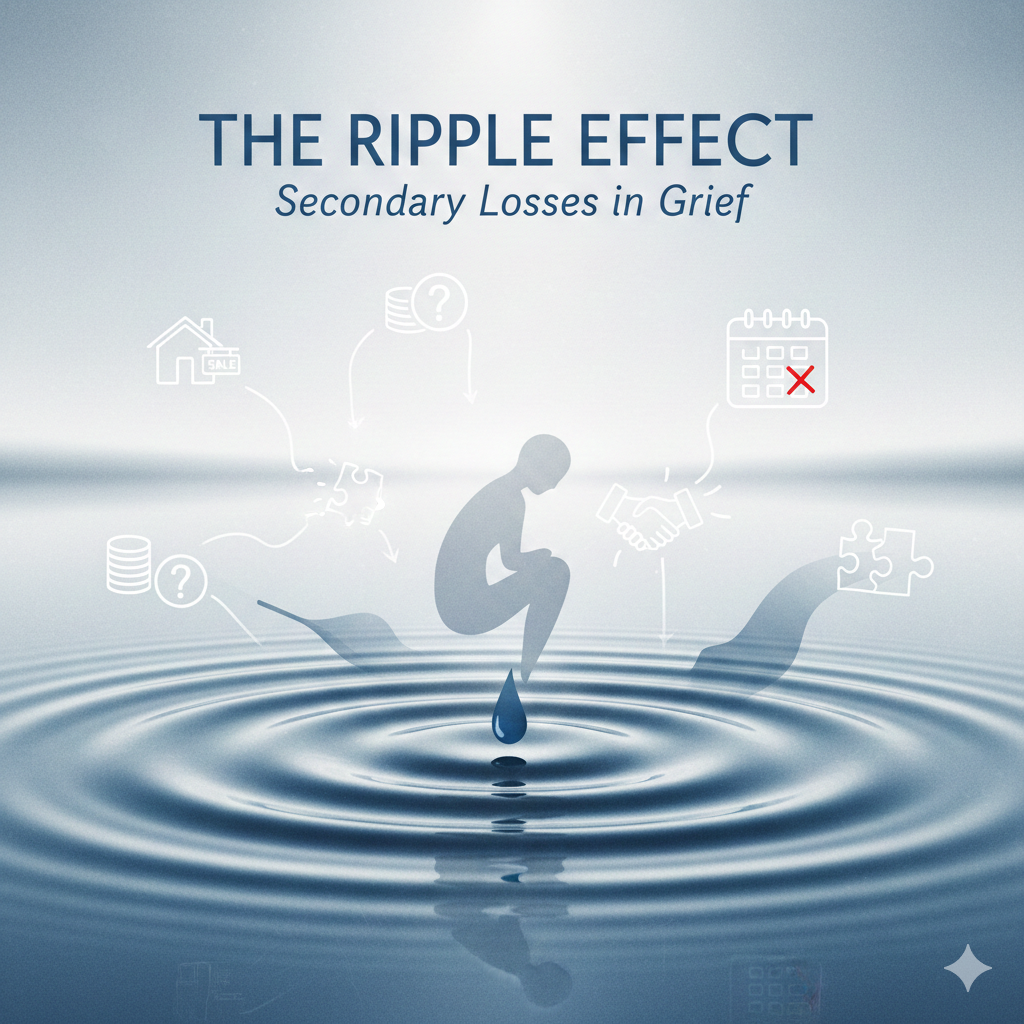

The Ripple Effect: Understanding Secondary Losses in Grief

When we talk about grief, the primary loss—the death itself—is immediately obvious. However, the profound impact of grief is often magnified by what we call secondary losses. These are the non-death related losses that ripple out from the primary loss, fundamentally affecting our lives in a myriad of ways.

What are Secondary Losses?

A secondary loss is the loss of tangible or intangible elements of life that were connected to the deceased or their role. These can include:

Loss of Identity: The deceased may have been a spouse, a parent, a close friend, or a caretaker. When they are gone, the survivor loses the corresponding role: "spouse," "parent," "caregiver," or "friend." This may force a painful reconstruction of self.

Loss of Financial Security or Lifestyle: The income, insurance, or general financial contribution of the deceased can vanish, leading to stress and significant changes in how the survivor must live.

Loss of Social Circle or Support: Friendships maintained through the loved one may fade. Shared activities, traditions, and routines—like Saturday morning coffee or holiday planning—cease. We may feel like the proverbial “third wheel” and no longer belong. Further, deaths may affect familial relationships, increasing emotional intensity and conflict.

Loss of Dreams and Future Plans: The shared future the grieving person envisioned—retirement, a child's graduation, a special trip—is suddenly unattainable.

Loss of Trust: The death of a loved one can often challenge our worldview and shatter our beliefs that life is predictable or fair. We may feel unsafe in the world, become hypervigilant, and question relationships and support systems.

Acknowledging these losses is a crucial step towards coping with loss. As we cope, we integrate our grief and restore our capacity for well-being. Ultimately, this allows us to see possibilities for a promising future and navigate a life that is meaningful to us.

Dosing Your Grief: Healthy Breaks and the Power of 'Puddle Jumping'

In the challenging landscape of loss, many of us feel pressured to be constantly immersed in our deepest pain—as if taking a break is a sign of avoidance or that our pain is our connection with the person who died. But what if "dosing" your grief—managing the intake of intense emotion—is actually a healthy, necessary form of self-regulation?

I see the benefits of this approach daily in practice. It’s a process distinct from total suppression; it's about conscious, temporary moderation.

The Art of the Emotional Break

When we talk about "dosing" grief, we are recognizing the limits of the human nervous system. As pioneer of loss and death studies Dr. J. William Worden noted in his four tasks of mourning (one of the evidence-based models of grief), grief work is demanding and needs to be balanced with periods of respite. We simply cannot process the full intensity of loss 24/7.

Healthy dosing allows you to:

Prevent Emotional Burnout: Deep sorrow is exhausting. Taking time to focus on daily tasks, hobbies, or light social interaction acts as a crucial energy renewal, allowing you to return to the grief work with more stamina.

Integrate Gradually: Grief is not a switch; it's a dimmer. Dosing allows you to slowly integrate the reality of the loss into your life without being completely overwhelmed or feeling shattered all at once.

From Avoidance to Puddle Jumping

The difference between healthy dosing and harmful avoidance is intentionality.

Avoidance (Suppression): Burying feelings, pretending the loss didn't happen, or using destructive behaviors (like excessive drinking) to numb all emotion. The grief is never acknowledged or addressed.

Dosing (Puddle Jumping): This term is often used in child grief work to describe how children naturally dive into their sorrow (the 'puddle') and then leap out to play, only to return later. Adults can adopt this, too. It means intentionally stepping away from the pain for a planned period—maybe watching a comedy, spending time with friends, or focusing intensely on a project—knowing that you will check back in with your feelings later.

Puddle jumping is an act of agency. It confirms that you are in control of when and how you engage with your pain, rather than letting the pain control you. It’s a rhythmic process of acknowledging the sorrow and choosing joy (or calm) when you need it most.

Give yourself permission to take these necessary breaks. Your strength isn't measured by the depth of your continuous sorrow, but by your capacity to regulate and navigate the waves of loss over time.

Grief and Holidays

For those of us who are grieving, the holiday season rarely lives up to the picture-perfect ideals seen on cards and screens. Following the death of a loved one, the traditional holiday focus on joy and togetherness can feel incredibly challenging.

It is important to put your feelings into perspective. Holiday pressures are real, causing stress even for those not currently grieving. When you factor in loss, that stress level can skyrocket. Do not judge your own emotions. Whether your loss was recent or long ago, a wide range of emotions—sadness, anger, exhaustion, or even surprising moments of peace—are "normal."

Flexibility and preparation can be helpful tools to navigate the holiday season. You can take control by making specific plans and securing the support you need before the season begins. Here is a link to the Griever’s Bill of Rights from the Heartlight Center that may help you understand and express your needs and hopes.

Also, do your best to prioritize self-care. Your physical well-being is closely tied to your emotional resilience. Make sure to eat regular, nourishing meals, get adequate rest, and avoid using alcohol or other substances to self-medicate or numb your feelings.

The Road Less Traveled: Grieving a Lost Future

Life, in its often-unpredictable way, constantly presents us with a myriad of paths. Each decision we make, each fork in the road we take, inevitably means leaving other paths untrodden. While we often celebrate the journey we embark on, there's a quieter, less acknowledged form of grief that many experience: grieving a lost future, the echo of "what might have been."

This grief is not necessarily about regretting choices, but rather acknowledging the very real sense of loss for a future that, for whatever reason, never materialized. It could be the career path you meticulously planned but had to abandon due to unforeseen circumstances. Perhaps it's the vision of a life with a person who died, or the dream of a particular family dynamic that shifted. It might even be the version of yourself you envisioned becoming, a self that was sidelined by life's detours.

The "road less traveled" often sounds romantic, but sometimes, the pain comes from not taking that road, or having it taken from you. We invest emotions, hopes, and dreams into these imagined futures. They become part of our identity, even before they become reality. When those futures vanish, whether through a breakup, a career setback, a health crisis, or simply the passage of time, the emotional residue can be profound. It’s the mourning of possibilities, the quiet ache for experiences that will now never be.

Allowing yourself to grieve these lost futures is just as important as grieving other losses. It's not a sign of weakness or a failure to accept your current reality (I will write about the importance of acceptance, or more accurately radical acceptance, in a future post). Instead, it's an acknowledgment of your capacity for hope, planning, and love. Give yourself permission to feel whatever emotions may arise - sadness, disappointment, and even the anger that can accompany such a loss. Talk about it if you can, write about it, or simply sit with your emotions.

While the future you envisioned may no longer be, recognizing and honoring that loss can help you move forward, not by forgetting, but by integrating that experience into your life. It clears the space for new possibilities, new dreams, and new futures to emerge. The echo of what might have been doesn't have to be a haunting; it can be a reminder of your incredible capacity to dream and to adapt.

See My Grief

I have written about how our death adverse society may isolate someone who is grieving. This isolation can be especially acute when our loss is not one that is openly acknowledged or socially supported. In those case, we may experience what is known as “disenfranchised grief,” a term coined by grief expert Kenneth J. Doka to describe grief for a loss that society does not grant the same validity or legitimacy as other, more recognized losses (such as the death of a spouse or parent). Because the bereaved person's grief is deemed insignificant or inappropriate by others, they often lack the crucial social support necessary for healthy mourning. This invalidation forces the person to grieve in isolation or silence, which can significantly complicate the grief journey, leading to feelings of isolation, anger, and confusion.

The lack of recognition can stem from the relationship being unrecognized (e.g., an affair), the loss itself being unrecognized (e.g., miscarriage), the griever being considered incapable of grief (e.g., a young child or a person with a cognitive disability), or the way the person died being stigmatized (e.g., suicide or an overdose). The lack of validation inherent in disenfranchised grief can prevent the individual from engaging in necessary grieving rituals and openly expressing their pain. The expectation to "just get over it" or to hide the true source of their distress makes it difficult to process the emotions associated with the loss. A common example is the grief experienced by a co-worker or an ex-spouse after a person's death; since the relationship is not considered "primary family," their sorrow is often overlooked in favor of the immediate next-of-kin, despite the deep bond and history that may have existed.

We often see disenfranchised grief following a death by suicide. For survivors of suicide loss (often called "suicide bereaved"), their grief is often compounded and complicated by a powerful surrounding stigma that minimizes or invalidates their right to mourn openly. This societal judgment, often rooted in historical or religious beliefs that cast the act of suicide as immoral or sinful, can cause the bereaved to feel intense shame, guilt, and isolation. They may hide the true cause of death to avoid judgment, leading to a profound lack of the necessary social support that typically helps individuals process a major loss.

How do we support someone who may be experiencing disenfranchised grief? The single most important thing you can do is acknowledge that their loss is real and their feelings are legitimate, regardless of how society views the situation. Acknowledge and use specific language: Instead of generic "I'm sorry for your loss," use language that recognizes the specific relationship or circumstance. It is also critical to avoid minimizing statements (often used following a miscarriage or stillborn death). Steer clear of trite phrases or comparisons. Your goal is to meet them where they are. Avoid: "At least you can try again," or "It was just an ex, you'll meet someone new." And, finally, check In consistently: Reach out days, weeks, and months later.

Pets and Grief

The bond we share with our pets is one of unconditional love, comfort, and routine. They are family members, confidantes, and constant presences in our lives. When that bond is suddenly broken, the emotional fallout can be devastating, often mirroring the pain experienced after the loss of a human loved one.

It’s crucial to understand that the grief process for a pet is fundamentally similar to any other loss. You may be experiencing a wide range of emotions, including intense sadness, denial, guilt, and anger. The guilt might stem from second-guessing medical decisions or the circumstances of their death, while anger might be directed toward the world for taking them too soon. These turbulent emotions are a normal and natural part of your grief journey.

It is also important to remember that grief is not just emotional; we experience physical changes and our brain struggles to make sense of a loved one’s absence (for a great exploration of grief and biology, I highly recommend Mary-Frances O’Connor’s books, The Grieving Brain and The Grieving Body). Many of my clients report brain fog, challenges with sleep, and fatigue.

The absence of our routines—the morning greeting, the daily walk, the evening snuggle—creates a vast, painful void. Acknowledging your intense, multifaceted grief is one of the important tasks of mourning. Give yourself permission to mourn fully and openly, just as you would for any significant loss. Be kind to yourself, seek support, and honor the deep love you shared.

The Toll of Dementia Caregiving

The majority (80%) of people with dementia are receiving care in their homes. To put this in perspective, 16 million Americans provide more than 17 billion hours of unpaid care for their loved ones. It is notable that dementia caregivers provide care for a longer duration than caregivers of people with other types of conditions.

Caregiving takes its toll and this is especially true for dementia caregivers. Dementia caregivers report higher levels of stress, more depression and anxiety symptoms, and lower levels of subjective well-being, self-efficacy, and anxiety. Further, caregivers experience worse physical health outcomes, including higher levels of stress hormones, compromised immune response, antibodies, greater medication use, and greater cognitive decline.

So what can we do?

There are protective factors for stress and depression: Larger social networks, frequent social contact, and the ability to arrange for assistance from friends are moderators of depressive symptoms and caregiver burden. Respite care is especially important. Research shows that even a few hours of respite a week can improve a caregiver’s well-being. Respite care can take the form of different types of services in the home, adult day care, or even short-term nursing home care so caregivers have a break or even go on vacation.

It is critical that caregivers make their needs known. For example, identify a caregiving task or a block of time that you would like help with. Perhaps there’s a book club meeting you’d like to attend or some time alone to read a book. Be ready when someone says, “What can I do to help?” with a specific time or task, such as, “It would be really helpful for me if you could stay with mom on Tuesday night so I can go to my book club for 2 hours.”

Be understanding if you are turned down. The person may not be able to help with that specific request, but they may be able to help another time. Don’t be afraid to ask again. If you have trouble asking for help face to face, try writing an e-mail to your friends and family members about your needs. Set up a shared online calendar or scheduling tool where people can sign up to provide you with regular respite.

Need more suggestions or resources? Boulder County offers support for caregivers through its AAA Caregiver Initiative. Alzheimers.gov provides helpful tips for dementia caregivers.

Can an Adult be an Orphan?

In the often cringe-worthy but hilarious show, Curb Your Enthusiasm, the lead character Larry David challenges his friend Marty Funkhouser’s statement that, with the death of his mother, he is now an orphan. "An orphan? You're a little too old to be an orphan."

I suspect that Larry’s reaction is not uncommon. Indeed, since it is expected that adult children will survive their parents, there is often the belief that when an elderly parent dies, “it’s no big deal - just part of life.” Unfortunately, the failure to recognize the impact of a parent’s death, regardless of the age of the child, can lead to disenfranchised grief, i.e., grief that is not openly acknowledged, socially supported, or publicly mourned.

This is tragic because, regardless of your relationship with your parent, their death can trigger strong emotions: sadness, relief, anger, guilt, regret. Further, there is a finality when both parents die that can shake our world. One client phrased it especially well: “When one parent dies, it’s a semi-colon. When the second parent dies, it is a period.”

The death of our parents can bring families closer to together and move them farther apart. Many times our parents are the “glue” that keeps a family together and, with their death, old wounds become raw again.

We also can experience a loss of identity and find new roles emerge. We may feel that we are no longer someone’s child. We may grieve the fact that we will have unanswered questions about our parents’ lives and history, or feel unable to resolve longstanding challenges.

As with all grief journeys, it is important to remember you have the right to express and experience your grief in your own way, including the right to express and explore your feelings. It may be helpful to note when you engage in rumination about what we “should have” done differently and accept that we did our best in the moment. And always remember there is no expiration date on our grief.

Children and Funerals

I am often asked by parents whether their children should attend a loved one’s funeral. Parents may be concerned the child will become overwhelmed or “too sad” if they attend. And, of course, there is the societal discomfort with grief and mourning generally that can color our views. It is important to note that children often feel excluded when they are not permitted to attend a funeral and may feel confused or resentful at the exclusion. Further, funerals serve an important role in the grieving process and allowing a child to attend may support their healthy grieving journey.

Having said all of this, there is no hard and fast rule – child participation should be guided by your child’s personal choices and your understanding of their needs, coping skills, and maturity. When deciding whether a child should attend, start with a conversation with your child. Share some basic details about what they may expect at the funeral (e.g., open casket, rituals, graveside internment). Discuss how people may react, including you and other loved ones. It is important to help your child understand that if someone is sad, quiet, or crying, they are showing their sadness and they are still okay. If it is appropriate for their age and maturity, allow your child to choose what parts they want to attend or skip. And, as always, avoid euphemisms (e.g., “passed away,” “resting in peace”) when discussing death – euphemisms tend to be confusing for children especially for those who are still grappling with ideas surrounding object permanence and the finality of death.

Here are two links for more thorough discussions regarding children and funerals that you may find helpful:

https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/good-mourning/201805/should-children-attend-funerals

https://riseandshine.childrensnational.org/preparing-your-child-for-a-funeral/

.

The Challenge of the Uncomfortable Friend/Family Member

We live in a death adverse society. Most people die in hospitals or facilities away from the home and the community. We treat death as a taboo subject preferring silence or euphemisms such as “passed away” to avoid the stark language of “death” and “dying.” Often people who are grieving feel pressure to “move on” or “get over” their grief.

One of the tragic consequences is that you may feel isolated following the death of a loved one because your friends and family seem to disappear. There are several reasons for this. They may be uncomfortable with their or your emotions. They may find it difficult to be around you especially when you share emotions such as sadness, anger, and guilt. Often people will avoid the subject of death because they worry about upsetting you. Others feel the need to be a “fixer” and and say things like: “Everything happens for a reason” (they don’t), “try to be positive” (i.e., don’t feel or show emotions that make me feel uncomfortable), “it’s time to move on” (I’m uncomfortable with your grief).

For those of us grieving, it falls to us to educate friends and family members about our grief journey. Some of the things we can do include: (1) Letting people know how they can help (be specific); (2) assuring people that it’s okay to talk about your loss and to ask how you’re feeling (if it is); (3) saying when you want company and when you want to be alone; and (4) telling people know there’s no expiration date on grief.

Grief - When Will I Feel Better?

It all begins with an idea.

When we’re in the depths of grief, we can feel overwhelmed, unsteady, and rocked by deep emotion. It’s therefore understandable that one of the most common questions I get as a grief therapist is, “when will I feel better?” The answer can be unsatisfying because grief is not linear and there are no stages of grief (contrary to outdated “stages” espoused by Dr. Kubler-Ross). Rather, we each have a unique grief journey and while we ultimately learn to incorporate death and loss into a meaningful life, our grief never ends because our connection with our loved ones never ends. Having said all of this, people will feel “better” over time as they discover a balance between grieving their loss and living a fulfilling life.